Two sermons for the First Sunday after Christmas

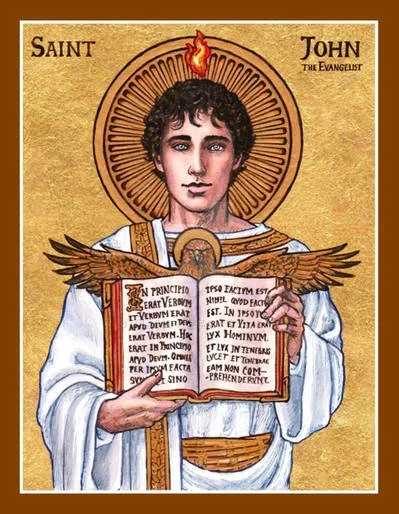

Today is the Feast of St John the Evangelist, who gave us the remarkable Prologue we will hear tomorrow. Here are two sermons I’ve preached on the Prologue to John on the First Sunday after Christmas Day.

First Sunday after Christmas

Cathedral Church of St Peter, St Petersburg

28–29 December 2019

✠ I speak to you in the Name of God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Amen.

The Word became flesh and lived among us.

He pretty much had to.

Not for his own sake, for he was with God, and was God, and needed nothing more than the everlasting fellowship of unstinting love, perfectly bestowed and perfectly received, that is the life of the Triune God.

No, not for his sake, but for ours. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being, including us, spoken into being by the eternal Word. And though he did not need us, we needed him. We need—oh, so many things—but surely one thing that we need, and would have needed even had our first parents not fallen into sin and become subject to evil and death, is particularity.

The eternal Word did not make us to float free above time and space, to be nourished by abstractions and to make our dwelling-place in a world of disembodied ideals. The eternal Word made us creatures of flesh and blood, rooted in a place and a time, sustained by food and drink and kind words and the touch of a gentle hand, who learn from parents and teachers, from particular things we see or hear or touch.

Theologians like to speak of the “scandal of particularity”—the outrageousness, the offensiveness, of the claim that the way to salvation is this man, born of this woman, born under this law. But it is no scandal. It is the most natural, the most inevitable, thing in the world: cataclysmic, yes, and we do well to fall on our knees in wonder and gratitude when we speak of it—and yet, as one of our deepest Incarnational theologians has said, “How silently, how silently the wondrous gift is given,” his love so relentless, our need so great, that it is the most obvious thing in the world for the Word to become flesh and move into the neighborhood.

How could it be otherwise? A universal ideal, however worthy, cannot motivate us, because we are creatures of flesh and blood. We can marinate ourselves in noble sentiments and congratulate ourselves on the correctness of our ideals, but they are impotent unless they are—there really is no other word for it—unless they are incarnate, made concrete and particular and here-and-now. Otherwise they cannot move us.

So the Word—who was with God, and was God, and is God—had to become flesh, so that our need for particularity could be met by the only ideal worthy of allegiance, the universal good, the fount of every blessing, the one through whom all things were made, God himself.

For make no mistake: we will get that need met somewhere. If we do not get it met by God, we will seek to meet it by allegiance to an

-ism, or commitment to a cause, or fanatical devotion to a person, by idolizing celebrities, even fascination with exotic spiritualities, cards and crystals and who knows what else. But anything short of God is too small to meet our need—yet God is too big for creatures like us. So the Word becomes flesh and lives among us.

And because our hope and salvation does not lie in abstractions—in “the ground of being” or “radical inclusion” or “catholicity” or “tolerance” or whatever it might be—but in this man, Jesus, the Word made flesh, we have to be prepared for surprises and, yes, even for disappointment. People are like that, aren’t they? They have their character and personality, their particularities and peculiarities, and they go about their lives being what and who they are, in the most ill-regulated way, not conforming to our whims as if they were fictional characters we get to make up, but confronting us at every turn with a solidity and reality and independence that is not of our own making and not under our control. The Word made flesh, Jesus, must be like this too; and to be in relationship with Jesus is inevitably to bump up against ways in which a human life divinely lived doesn’t conform to our expectations.

We see this in both Matthew and Luke, when even John the Baptist—the very man sent by God to testify to that light—sent his disciples to ask Jesus, “Are you the one who is to come, or are we to look for another?” John had preached that the one who was to come would bring the holy wind that would separate the wheat from the chaff, and the fire of judgment that would purge and burn away the chaff, the wicked, the unrighteous, the unrepentant. And then Jesus came, and where was the judgment? Where was the fire?

We probably don’t look to Jesus for fiery judgment. (We’re Episcopalians, after all; we’re really not into that kind of thing.) But we may look to Jesus for a political program—our political program, the one we would support even if it weren’t for Jesus, but we expect Jesus to sign on for it. Or we look to Jesus for a moral code— our moral code, the one we would support even if it weren’t for Jesus, but we expect Jesus to sign on for it. We want a Jesus who represents some ideal to which we give our allegiance.

But the saving truth is not that our ideals have acquired a spokesman. The saving truth is not that our aspirations have found a salesman. The saving truth is that the Word has become flesh, God was made man, and that God-man is surprising, and challenging, and as real and particular as any other human being.

He is not going to be anyone other than who he is. He can’t be—real flesh-and-blood people don’t effortlessly conform to our expectations. He is not going to conform to us. So we will have to conform to him. If we are to be saved by this man—this man, born of this woman, born under this law—then we will have to conform to him. And there is no salvation in any other Name, because he alone is divine and human, and anything less than God is too little for us, and anything greater than humanity is too big. So if we are to be saved, we will have to conform to him.

Very well. Let’s get right to that, shaping our minds by professing our faith in him, shaping our desires by speaking to him in prayer, and finally shaping our very being by taking him into ourselves—the Word made flesh, made bread and wine— so that we may become what we eat, and share the divine life of him who humbled himself to share our humanity, even Jesus Christ our Lord, to whom, with the Father and the Holy Spirit, be ascribed, as is most justly due, all might, dominion, majesty, and glory, world without end. Amen.

First Sunday after Christmas

Cathedral Church of St Peter, St Petersburg

31 December 2023

✠ I speak to you in the Name of God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Amen.

“In the beginning,” the educated first-century Jew hears, and thinks, “Ah, I know where this is going.” “In the beginning God created,” where “in the beginning” means “at the outset, when time first got started.”

“In the beginning,” the educated first-century Greek hears, and thinks, “Ah, I know where this is going.” “In the beginning” is good philosophical Greek for “at the deepest level of all things, at the source of all being.”

The Jewish listener is sure that we’re in for a creation story; the Greek listener is sure that we’re in for a philosophical treatise on the ultimate principle of reality. “Ah, I know where this is going,” they both think: but they don’t know where this is going, can’t know, because this is going somewhere no creation story, no philosophical treatise, has ever gone before.

In the beginning—both at the outset of time and at the deepest level of reality—was the Word. “By the word of the Lord were the heavens made,” so this is still a creation story; and the Word is also the rational principle that unites all things and gives them meaning and purpose, so this is still a philosophical treatise. The educated first-century Jew and the educated first-century Greek are still on board.

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. And somewhere in there the educated audience begins to raise its eyebrows and squirm in its seats. If the Word—the Word by which the heavens were made, the Word that unites all things and gives them purpose—is with God, then fine: the Word is the self-expression of God in creation. But God’s self-expression isn’t God. God’s self-expression in creation is limited, time-bound, imperfect, ever-shifting: God is none of those things, as Jews and Greeks agree. So the Word can be with God, but the Word can’t be God.

Not to mention, as any self-respecting Jewish theologian or Greek philosopher knows perfectly well, God is One—hear, O Israel, the Lord your God, the Lord is one. But if the Word is with God, and the Word also is God, then it really does look like you have two gods on your hands—and we haven’t spent all this energy fighting against polytheism and Greek popular religion to revert to that nonsense at this late date.

The Word was with God, and the Word was God. The life of the Word is divine life, but it is not the whole of divine life. The self-revelation of God is the beginning and the source of all things, but there first must be a self to be revealed.

And now I’m in danger of preaching on the Trinity when it isn’t even Trinity Sunday, so let me file that away, because that’s not where John the Evangelist is taking this new story, which is going where no creation story and no philosophical treatise had ever gone before.

The Jewish theologian and the Greek philosopher could both, in their own ways, affirm that the divine self-revelation that is the beginning and the source of all things is expressed in creation. But John the Evangelist wants us to go further. The self-revelation that is in the very heart of God’s being is already complete, already perfect, before there is any creation at all. In the beginning, before there is even such a thing as “before,” there is the Word, God with God. God fully expresses the divine nature—the Word fully interprets the being of God—before the voice of God shatters the silence and speaks light into the dark and menacing void. The Word is not—sorry, theologians; sorry, philosophers—but the Word is not the mechanism of creation or the rational pattern of creation; no, the Word is the agent of creation: “All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being.”

What comes about through the Word is the whole realm of time and change, of imperfection and incompleteness, which is all somehow, nonetheless, the arena of God’s self-revelation. But over against that realm of time and change is the timeless and unchanging Word, the perfection of God’s self-revelation before the creation story even begins, before there is such a thing as “before.” Saint John sets the two things side by side and says to the philosophers, “Your rational principle of all things is no abstraction, but a divine person, God with God.” He sets the two things side by side and says to the theologians, “The world interprets God to us only because the perfect Interpreter, the perfect Interpretation, has made it that way.” He sets the two things side by side and doesn’t even try to tell us how that works, to solve the intellectual problems that this startling new picture poses for us.

No, he doesn’t try to solve the problems. He deliberately goes on to make the problems worse. Because the eternal Word and the time-bound world do not simply coexist, one depending on the other, but hermetically sealed off from any contact. That would at least be philosophically and theologically respectable. No, the eternal Word interprets God all the way right down into the world of time and change and imperfection. The Word becomes flesh: a disgrace and an offense from which every sensible and high-minded person very properly recoils.

God, however, is not a sensible and high-minded person. And all the messiness of flesh—all the frailty and pain and need, but also all the joys and laughter and friendship—became part of the experience of the very Word of God, and to those who had eyes to see, Saint John tells us, it looked like glory, glory as of a Father’s only Son.

Over the years, though, even to some who profess and call themselves Christians, it hasn’t looked like glory. Some of the mystics have written as if we should be embarrassed by our fleshliness. Why? Jesus isn’t. Some of the theologians have written as if we should ultimately seek to lose our individuality in the divine. Why? Jesus didn’t. He was God with God: one with God, yet wholly himself, the Father’s only Son.

Only Son by nature, that is. Saint Paul tells the Galatians that God sent his Son—that the Word was made flesh—to make us by adoption what he already was by nature. He took upon himself the messiness of flesh not only so that we could behold his glory, but so that we could share it. Jesus, in his flesh, in his particularity, used a word to address his Father. It was not some universal, heavenly speech, unutterable by human tongues. He used the language of his family, a particular, historical, contingent language just like the languages we all use, and God-with-God called God “Abba,” which was Aramaic for Father. And thanks to Jesus, Paul says, so can we. Because the Word made flesh has given us the power to do so: not by imposing a law, but by infusing a Spirit, his Spirit. Just as John the Evangelist also said: “to all who received him, who believed on his Name, he gave power to become children of God.”

This is not where any creation story, any philosophical treatise, had gone before. Father, Word, and Spirit, all God—see, I can’t keep away from the Trinity—at work in the world of time and change, of human frailty and human glory, not to erase it, not to make it anything other than what the Word made it to be, but to affirm it in its particularity, to meet its need by the only good at once big enough to satisfy it and small enough to look it in the eye, so that we might share the divine life of the eternal Word who humbled himself to share our humanity, and in the power of the Spirit cry out, in our own imperfect voices, in our own particular languages, “Abba! Father!”

And so to Father, Word, and Spirit, one God, be ascribed, as is most justly due, all might, dominion, majesty, and glory, world without end. Amen.